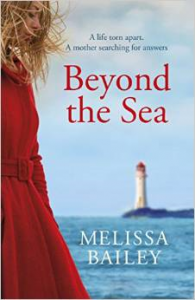

I’m delighted to be interviewing fellow Prime Writer, Louise Beech about her third novel, Maria in the Moon (published by Orenda Books on Kindle on 15 August and in paperback on 30 September). It’s a dark, beautiful novel of self-discovery and focuses on Catherine Hope an inimitable heroine who has many names and many sides – as Catherine she is the truculent and defensive step-daughter, as Katrina, she is the caring and sensitive Crisis line worker, as Catherine-Maria she is the sweet innocent child beloved of her Nanny Eve. But who is she really? She more than anyone wants to know. Yet while she can remember a great many things – including the birthday of practically everyone she’s ever met – the whole of her ninth year is a blank. But as the murky floodwaters that devastated Hull in 2007 subside, long-forgotten memories begin to surface and Catherine starts to uncover long-hidden truths.

Louise, I loved this novel and particularly how you wove together the Hull floods, Catherine’s work on a Crisis line – which rings so true I feel there must be some personal experience there – and the emergence of Catherine’s repressed memories. Can you talk a little about how the original ideas for the novel came to you?

Thank you, so much. It was a highly personal novel. I wrote it just after we’d been flooded in 2007, while my daughter was very ill (just diagnosed with Type 1 Diabetes) and having given up my day job in travel to be there for her. All I had while she was at school was time; time I didn’t want as it meant facing what had happened, facing my own past in many ways, and being in a rented house I hated while our own home was rebuilt. And so I started writing. The words poured out of me. Catherine came to me vividly. This lost woman, fighting hard, angry and sad, surviving and failing. I used my experience as a Samaritans volunteer, and of course how it had felt to see my home destroyed. In my novels, I seem to lay myself bare while hiding also. Much of my fiction comes from truth – as in experience – but yet I often get lost in what is memory and what is made up. At the moment I’m exploring repressed memories of my own and so it’s quite profound that this novel is coming out now. So, this book, in many ways, is my most personal yet

This book is darker than both of your other novels, How to be Brave and The Mountain in My Shoe, and at times it’s a difficult book to read. Was it a difficult book to write?

Emotionally yes, but physically no. Because it was so personal, it often made me cry to write it. But with regards the story ‘coming out,’ I had no trouble. It flowed and was probably the novel I wrote the fastest. It was intense though because obviously I was going through a really dark time while writing it, and also my backdrop was the sound of hammering and drilling as flood homes were rebuilt around me.

It is also interspersed with great humour – real laugh out loud funny scenes. Was that deliberate?

Haha, yes. But very natural to me also. I knew the book needed light moments, and anyone who knows me knows that I love to laugh and have fun. I laugh every day. It’s a common coping mechanism too. The more ‘rude’ I made Catherine, the funnier it got, and so I had a great time playing around with the comical relationship with her mother, especially their banter at Sunday lunch.

Maria in the Moon is being labelled a psychological thriller. Did you set out to write it as such?

I think we’re going to play with that term. Come up with our own. I like Psychological Drama. Or Dark Drama. Readers do often like to know what something is, which is understandable. The most difficult aspect of being published so far seems to have been finding where I belong. It was partly why I had so many rejections for so many years; I couldn’t sum up what I was. I didn’t know. I still don’t! I never set out to write anything as a particular genre. I just want to tell the story, and I suppose what will be will be. I really can’t write anything other than what demands to be written.

While definitely having the trademarks of a psychological thriller (pacy, with an unfolding mystery, and a brilliant twist at the end) this book is also so contemplative and beautifully written. Does this simply flow off your pen in a first draft or does it come in the editing of later drafts?

As someone who is hugely self-critical, I edit as I go. It’s almost not conscious, as in it’s naturally part of my writing process. My first draft is usually more or less what it will be, aside from tweaks and improvements and tightening and juggling the odd scene. Though, having said that, book four – The Lion Tamer Who Lost, out next year! – had the most major rewrite of all. I realised one of my main characters was gay, having written him as heterosexual, and so the entire novel had to be changed in a major way. Quite the challenge, but very exciting. When I sit down to write, I read the previous five or ten pages to get in the zone, and off I go. On a bad day, I don’t have time to write. It can be tough with all the events and promoting involved and still having a ‘day’ job. On a great day, I’ve been known to write 4000 words. Those are the days I clap my hands and dance, haha.

The concept of home and what that means is a theme that recurs throughout your novels. It’s very strong in The Mountain in My Shoe in the characters of Conor, the feisty yet vulnerable boy in care, and Bernadette, the abused woman who mentors him. You return to it with Catherine, homeless and rootless after the flood. Why do you think you are drawn to this subject?

This question really made me think the most. It’s a great question. I just didn’t realise I had explored this so much. And yet it makes total sense that I would. I had a pretty disruptive childhood. Lived in many places, due to my parents’ divorce and both of their mental health issues and problems. I was in care briefly, and lived with my grandma too, a hundred miles away from home. So, I often felt like I didn’t really belong anywhere. My feeling is that home is about the people rather than a physical place. Those we love. I always felt okay if I was with my siblings, though sadly my little brother was fostered separately from us for a year and that broke my heart. Almost more than being away from our mother. Now, as an adult and parent, one of the most important things for me is to create a lovely home for my family, and to do my best to keep them all safe.

And finally I wanted to ask you about the pull that water has for you. There’s the sea in How to be Brave and the estuary in both Mountain and Maria, as well as the floods. You seem to be drawn to it?

Yes. I do. I LOVE the water, both the sea and rivers. Being on it. Being close to it. Being able to hear and smell it. I reckon my grandfather’s merchant seaman blood pulsates through me too! I think this is why the floods of 2007 affected me so deeply – the very thing I loved had attacked me. Wrecked all that I had. I still get anxious when I hear the rain. But my love of the sea remains.