Ten miles from shore, perched on the low black rock, the lighthouse was a hazy smudge of white in the gloaming. Isolated, indistinct, hovering somewhere between sea and sky, an as-yet unlit beacon of hope and salvation, it waited in the gathering darkness for its keepers to go to work.

8 pm

‘Come on, slow coach.’ Stan’s voice was loud, jovial, bouncing off the rough granite and echoing up the tower until it was swallowed by the growing sound of the wind. Something big was on its way and no messing. He gazed down at George, who was following behind him.

‘I’m a coming,’ the older keeper muttered. But instead he stopped and looked through the small window. Outside the sky was feverish. Clouds whirled at dizzying speed and below the waves churned, seeming to double in size as he watched. He remembered how Stan, when he was new to the service, had asked a number of times whether the lighthouse might topple in a gale. He’d been afraid, George had sensed, although the question had always been put light heartedly. Impossible, George had answered over and over, yet he suspected that the fear remained. But rather than give in to it, Stan laughed instead. That’s what he always did. He laughed at what scared him. And, somehow, that always made George feel better.

‘Come on, will you,’ Stan called. ‘It’ll be dark and the bloody light still won’t be lit.’ He spun on his heels and almost overbalanced. Placing his hand on the shallow ceiling for support, he avoided grabbing the brass handrail.

‘I’m a coming,’ George said again, resuming the long march upwards. But he too refrained from touching the railing.

It was unspoken but nonetheless they had reached agreement on it. Fingerprints don’t polish themselves out, after all.

12 am to 4 am

Strictly speaking this was George’s watch – his turn to keep the light unclogged and burning. But Stan invariably kept him company. He’d never needed to sleep much, or so he said. For which George was silently yet eternally grateful. This watch, the middle, was the worst. A strange time where, if a man was alone at the top of this tower, the gloomy imaginings that were anchored deep during the day could float free. He could find himself believing that he was the only man left in the world and everyone he cared about had disappeared. George swallowed and watched the sweep of the lamp. It flashed twice, puncturing the blackness for a few seconds. Then there was only the unbroken dark.

‘Bloody Nora.’ Stan burst through the gallery doors, slamming them shut behind him. ‘It’s going to take all night for this one to blow itself out.’ He crossed the lamp room and began scribbling notes in the logbook. After a moment he looked up. ‘Now stop with them bad thoughts, Georgie. Suze wouldn’t like it. A waste of bloody time, she’d say.’

Yes, she would have said that. In spite of himself George smiled and nodded. He looked at Stan: the shaved head, the strong stout body, the mermaid tattoo on his forearm that he’d got in prison. Yet it was curiously fitting for this, his new life, the one he’d fled to afterwards. The watery exile that seemed to suit him so well. At first George hadn’t been sure. But now he was fairly confident that Stan wouldn’t return to that life. A sense of relief flowed through him at the thought of it.

‘And guess what? Spot on I was with the wind force. Just from the feel of it on my cheek out there. Like you said, it’s something you come to know. Taught me well, you did.’ Stan winked at George as he sat down opposite him. ‘All I’ve got to do now is learn how to thrash you at chess. But I think that might take a bit longer.’

‘Check mate,’ said George, moving his rook with finality over the board between them. Then he started laughing. It was a warm, hearty laugh, but it caught in his throat and before long he was coughing, unable to stop.

The shadow of a frown crossed Stan’s face but it was gone before George could register it. ‘You’d better get that checked out when we go ashore,’ said Stan, reaching over and patting him on the back.

‘I’m fine, it’s nothing,’ said George, taking a swig of tea from his mug. ‘Gloating never suited me, that’s all.’

Stan grinned, looking at the old man. He was neatness incarnate, always polished, suited and booted, never a grey hair out of place. And he was a good bloke, taken him under his wing when he first arrived, for which God knows he’d been thankful though he found it hard to say. He’d worried a lot, after Suze died, about whether Georgie would retire from the service. But he thought it was unlikely now. Instead he worried about the other things that might take Georgie away.

Stan laughed loudly, seemingly at nothing, disturbing the quiet that had settled upon the room. ‘Well, Georgie, we’d better hunker down and wait this storm out. I’ll make another pot of tea while you set the board up again.’

‘Right you are then,’ said George. ‘And bring some of those chocolate digestives back with you. Then,’ and he began chuckling, ‘we’ll see if you can do any better this time.

Stan headed to the spiral staircase, with a quick backward glance before he began the race down. George was on his feet, keeping vigil, inspecting the lamp, nurturing the light that spilled into the darkness both in the lighthouse and beyond.

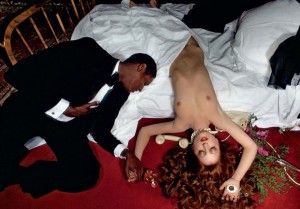

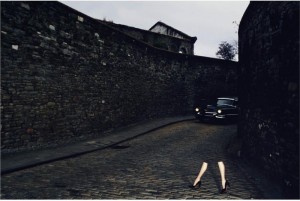

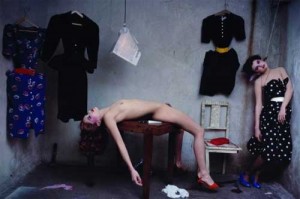

were often portrayed as supine, like mannequins, or merely sometimes as a pair of disembodied legs modelling shoes. His pictures were subversive, sinister, dangerous – the word ‘stiletto’, interestingly, means a blade or sharp knife in Italian – and in many images it is difficult to tell if the glassy eyed women pictured are dead or alive.

were often portrayed as supine, like mannequins, or merely sometimes as a pair of disembodied legs modelling shoes. His pictures were subversive, sinister, dangerous – the word ‘stiletto’, interestingly, means a blade or sharp knife in Italian – and in many images it is difficult to tell if the glassy eyed women pictured are dead or alive.