Somerset House recently housed the UK’s largest ever exhibition of the work of enigmatic and surrealist fashion photographer Guy Bourdin (1928-1991), containing over 100 colour exhibition prints of his most significant works. They said of Bourdin:

‘[His] editorial and advertising imagery represent a highpoint in late twentieth century fashion photography. His work took the basic function of the fashion photograph – to sell clothing, beauty and accessories – …but… established the idea that the product is secondary to the image. [He] made [fashion photography] into something rich and strange.’

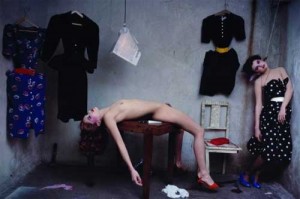

Rich and strange. That for me sums up the work of Bourdin. His narratives are dark, complex, sensual, sometimes sinister, always provocative. Some have an illicit, voyeuristic feeling to them, as if you are witnessing a moment that perhaps you shouldn’t. And it is not always clear what exactly it is you have seen.

For example, in this photograph two women lie beneath newspapers on a pile of sand while a third is seen in a phone booth, clearly alarmed. Are the two women dead? And is the third another victim, a witness or perhaps the assailant? Who knows.

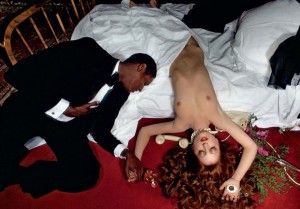

This image shows a pale naked woman, supine across an unkempt bed, a telephone cord twisted around her neck. Her hair drapes luxuriously across the floor – in one hand she holds a necklace, in the other the hand of the black man lying beside her. Is it a tryst gone wrong? Ecstasy followed by strangulation? Possibly. There are signs of struggle in the flowers which have fallen to the floor beside her. Or is it in fact self-inflicted death, the man having arrived too late to save her? It’s unclear, but the effect is disturbing. ‘They’re perverse,’ says Ophelia, a photographer in my novel, The Medici Mirror, when describing Bourdin’s influential images. ‘Glamour with a hint of danger.’ And I’d have to agree with her. They are seductive, challenging, but not always easy to view.

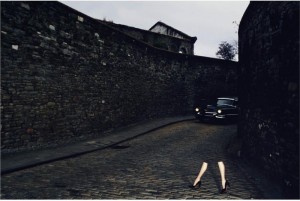

Many contain an overt tone of violence towards women and Bourdin’s critics have accused him of objectification and misogyny. In many images the models are compliant, glassy eyed, vacant, so stylised they take on the look of mannequins rather than real women. Shots focus on legs, the rest of the body simply invisible.

And in a number of photographs, only disembodied legs appear, striding down streets or beside the sea. Women’s body parts are fetishized, becoming things separated from the real person they were once attached to.

Perhaps Bourdin’s own troubled relationship with his mother lies behind this less than comfortable representation of women. Abandoned as a young boy, he only saw his mother once after this and admitted that he had never been able to forgive her. He recalled her as an elegant, red haired Parisenne with pale skin and relatively heavy make-up. It’s surely not coincidental that a recurrent model in his images perfectly matches this description. By all accounts, Bourdin grew into a needy, controlling man with a disturbing tendency to lock his girlfriends away in his apartment, keeping them closeted from the world. Two committed suicide – one from what was believed to be an overdose, another hanged herself.

Whatever you think of Bourdin the man, for me his images while shocking, scandalising and unsettling will remain always enthralling. What do you make of them?